Kevin Barry’s strange and touching Beatlebone (Canongate) brilliantly imagines a dreamlike road trip to the west of Ireland in 1978 by a hunted and haunted John Lennon. Despite the call of the several new novels on my shelf, I found myself rereading Edward St Aubyn’s extraordinary Patrick Melrose novels (Picador), and they were even better the second time around. As an Arsenal fan, I was never a lover of Roy Keane. But I loved his book, The Second Half (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), written with Roddy Doyle. Honest, self-critical and, along with Gary Neville’s Red (Corgi), a raising of the bar in the generally dodgy field of football autobiography. For Christmas, I would like all of Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir novels, and the additional gift of the time to read them.

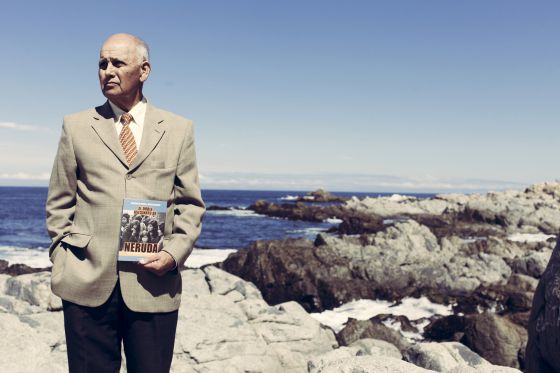

Maggie Gee

Closure: Contemporary Black British Short Stories; An Aviary of Small Birds by Karen McCarthy Woolf

The most important and exciting anthology of short stories published this year is Closure: Contemporary Black British Short Stories (Peepal Tree Press), edited by Jacob Ross, containing a range of stunning new writing, such as Leone Ross’s surreal story about the materialising of lost hymens in the street, “tiny, silken, throbbing things”. I also loved Karen McCarthy Woolf’s technically perfect poems of winged heartbreak, An Aviary of Small Birds (Carcanet Press). Christmas gift? Xavier Bray’s catalogue to the Goya: The Portraits exhibition (National Gallery), please.

The most important and exciting anthology of short stories published this year is Closure: Contemporary Black British Short Stories (Peepal Tree Press), edited by Jacob Ross, containing a range of stunning new writing, such as Leone Ross’s surreal story about the materialising of lost hymens in the street, “tiny, silken, throbbing things”. I also loved Karen McCarthy Woolf’s technically perfect poems of winged heartbreak, An Aviary of Small Birds (Carcanet Press). Christmas gift? Xavier Bray’s catalogue to the Goya: The Portraits exhibition (National Gallery), please.

Nicholas Hytner

The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks; 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear by James Shapiro

The Shepherd’s Life (Allen Lane) gives the finger to Wordsworth. James Rebanks seems never happier than when his hand is up a Herdwick sheep’s arse, but his book is a superbly written ode to an ancient way of life, and brought back childhood summers in the Lake District when I didn’t look hard enough. James Shapiro’s 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (Faber) brings to dazzling life the world from which sprang the best crop of new plays in theatre history. Robert Caro’s The Power Broker (Bodley Head) tells the Shakespearean life of Robert Moses, who, though officially not much more than New York parks commissioner, fills 1,200 pages with monstrous energy. For Christmas, I’d like James Rebanks’s new book The Illustrated Herdwick Shepherd (Particular Books).

The Shepherd’s Life (Allen Lane) gives the finger to Wordsworth. James Rebanks seems never happier than when his hand is up a Herdwick sheep’s arse, but his book is a superbly written ode to an ancient way of life, and brought back childhood summers in the Lake District when I didn’t look hard enough. James Shapiro’s 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (Faber) brings to dazzling life the world from which sprang the best crop of new plays in theatre history. Robert Caro’s The Power Broker (Bodley Head) tells the Shakespearean life of Robert Moses, who, though officially not much more than New York parks commissioner, fills 1,200 pages with monstrous energy. For Christmas, I’d like James Rebanks’s new book The Illustrated Herdwick Shepherd (Particular Books).

Lucy Hughes-Hallett

A Reunion of Ghosts by Judith Claire Mitchell; The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant is a hauntingly original meditation on mortality, in the guise of an Arthurian quest. What will survive of us is love, wrote Larkin: Ishiguro, a tougher thinker, suggests that love is as evanescent as ageing lovers’ frail bodies and faltering minds. Judith Claire Mitchell’s A Reunion of Ghosts has dark subject matter – suicide, the gas chambers – but the verve of the three eccentric New York heroines, cracking jokes into the jaws of death, give it an irresistible comic charge.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant is a hauntingly original meditation on mortality, in the guise of an Arthurian quest. What will survive of us is love, wrote Larkin: Ishiguro, a tougher thinker, suggests that love is as evanescent as ageing lovers’ frail bodies and faltering minds. Judith Claire Mitchell’s A Reunion of Ghosts has dark subject matter – suicide, the gas chambers – but the verve of the three eccentric New York heroines, cracking jokes into the jaws of death, give it an irresistible comic charge.

William Dalrymple

Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms by Gerald Russell; The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan

It’s a very long time since I read a travel book that has taught or illuminated so much as Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (Simon & Schuster), Gerald Russell’s brilliant and constantly engaging account of his travels through the disappearing minority religions of the Middle East. Tragically, this book puts on record for the last possible time a once plural world that is on the verge of disappearing for ever. BN Goswamy is to Indian art history what Sachin Tendulkar is to its cricket pitches or Shah Rukh Khan to its movies: a towering colossus who has transformed the nature of his chosen field, as well as being, at the same time, an irreplaceable national treasure. India’s most admired art historian combines in one elegant frame the eye of the aesthete, the discrimination of a connoisseur and the soul of a poet, with the rigorous mind of a scholar and the elegant prose of a gifted writer. His new book, The Spirit of Indian Painting (Allen Lane), is the summation of a lifetime’s loving dedication to his subject. It may well also be his most beautiful, and is his most heartfelt work too. But it’s Peter Frankopan’s massive 650-page The Silk Roads (Bloomsbury) that is my book of the year: history on a grand scale, with a sweep and ambition that is rare, especially in professional academia. This is a remarkable book on many levels, and one that anyone would have been proud to write: a proper historical epic of dazzling range, ambition and achievement.

It’s a very long time since I read a travel book that has taught or illuminated so much as Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (Simon & Schuster), Gerald Russell’s brilliant and constantly engaging account of his travels through the disappearing minority religions of the Middle East. Tragically, this book puts on record for the last possible time a once plural world that is on the verge of disappearing for ever. BN Goswamy is to Indian art history what Sachin Tendulkar is to its cricket pitches or Shah Rukh Khan to its movies: a towering colossus who has transformed the nature of his chosen field, as well as being, at the same time, an irreplaceable national treasure. India’s most admired art historian combines in one elegant frame the eye of the aesthete, the discrimination of a connoisseur and the soul of a poet, with the rigorous mind of a scholar and the elegant prose of a gifted writer. His new book, The Spirit of Indian Painting (Allen Lane), is the summation of a lifetime’s loving dedication to his subject. It may well also be his most beautiful, and is his most heartfelt work too. But it’s Peter Frankopan’s massive 650-page The Silk Roads (Bloomsbury) that is my book of the year: history on a grand scale, with a sweep and ambition that is rare, especially in professional academia. This is a remarkable book on many levels, and one that anyone would have been proud to write: a proper historical epic of dazzling range, ambition and achievement.

Mariella Frostrup

Keeping an Eye Open by Julian Barnes; The Kindness of Enemies by Leila Aboulela; Acts of the Assassins by Richard Beard

I really enjoyed Julian Barnes’s Keeping an Eye Open: Essays on Art (Jonathan Cape), which gave me a new confidence in how to engage with, understand and, more importantly, enjoy wandering around an exhibition. It opened the door to a new way of considering art that has subsequently given me a lot of pleasure, both in the reading and then in the doing. Leila Aboulela’s The Kindness of Enemies (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) was another treat – a novel that recreates the fascinating story of the rebel of the Caucasus, Imam Samil, a 19th-century warrior who battled to defend his home against the invading Russians and united the Muslims of the region under his iconic leadership. Weaving the story of his relationship with a Georgian princess he kidnapped into a more contemporary story of mistaken terrorism, we learn much about the nature of loss, the legacy of exile and the meaning of home at a time in our world when all three are high in our minds. Finally, Acts of the Assassins by Richard Beard (Harvill Secker) is a clever recreation of the events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus, told in a chorus of the apostles’ voices and making for one of this year’s most gripping and unusual thrillers, despite knowing the ending of the tale all too well. I’ve saved Salman Rushdie’s latest, Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty Eight Nights (Jonathan Cape), as a festive treat as I know it will bring light, warmth and humour along with a playful understanding of the vagaries of human nature – all of which are essential to endure a family Christmas.

I really enjoyed Julian Barnes’s Keeping an Eye Open: Essays on Art (Jonathan Cape), which gave me a new confidence in how to engage with, understand and, more importantly, enjoy wandering around an exhibition. It opened the door to a new way of considering art that has subsequently given me a lot of pleasure, both in the reading and then in the doing. Leila Aboulela’s The Kindness of Enemies (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) was another treat – a novel that recreates the fascinating story of the rebel of the Caucasus, Imam Samil, a 19th-century warrior who battled to defend his home against the invading Russians and united the Muslims of the region under his iconic leadership. Weaving the story of his relationship with a Georgian princess he kidnapped into a more contemporary story of mistaken terrorism, we learn much about the nature of loss, the legacy of exile and the meaning of home at a time in our world when all three are high in our minds. Finally, Acts of the Assassins by Richard Beard (Harvill Secker) is a clever recreation of the events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus, told in a chorus of the apostles’ voices and making for one of this year’s most gripping and unusual thrillers, despite knowing the ending of the tale all too well. I’ve saved Salman Rushdie’s latest, Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty Eight Nights (Jonathan Cape), as a festive treat as I know it will bring light, warmth and humour along with a playful understanding of the vagaries of human nature – all of which are essential to endure a family Christmas.

Richard Flanagan

Submission by Michel Houellebecq

Of the small number of books first published in 2015 that I have read, one I thought great, and all others seemed in its shadow. Michel Houellebecq’s Submission (William Heinemann) is many things: comic, profound, and at times unexpectedly moving. It is much more about human nature than Islam, and to think otherwise is to misunderstand it. Of the several suicide notes for the west Houellebecq has written, this is his best. As for Christmas, is it possible to receive not another book but the gift of time to read a few more of the books I already have?

Of the small number of books first published in 2015 that I have read, one I thought great, and all others seemed in its shadow. Michel Houellebecq’s Submission (William Heinemann) is many things: comic, profound, and at times unexpectedly moving. It is much more about human nature than Islam, and to think otherwise is to misunderstand it. Of the several suicide notes for the west Houellebecq has written, this is his best. As for Christmas, is it possible to receive not another book but the gift of time to read a few more of the books I already have?

John Kampfner

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami; The German War by Nicholas Stargardt

Loneliness, sexual ambiguity and emotional repression – the perfect recipe for a novel that put Haruki Murakami back on my list of unputdownable authors. In Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (Vintage), he tells the story of a young man mentally paralysed by the decision of his teenage friends to ostracise him. Eventually he goes in search of the answer, casting a riveting light on a country I never cease to be fascinated by. Equally riveting was Nicholas Stargardt’s The German War (Bodley Head), an immense social history that uses the diaries and letters from ordinary Germans, weaving a narrative that alternates from a love of Shakespeare, the horrors of the eastern front and love affairs, to minute accounts of complicity in the euthanasia programme of the disabled to the Holocaust.

Loneliness, sexual ambiguity and emotional repression – the perfect recipe for a novel that put Haruki Murakami back on my list of unputdownable authors. In Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (Vintage), he tells the story of a young man mentally paralysed by the decision of his teenage friends to ostracise him. Eventually he goes in search of the answer, casting a riveting light on a country I never cease to be fascinated by. Equally riveting was Nicholas Stargardt’s The German War (Bodley Head), an immense social history that uses the diaries and letters from ordinary Germans, weaving a narrative that alternates from a love of Shakespeare, the horrors of the eastern front and love affairs, to minute accounts of complicity in the euthanasia programme of the disabled to the Holocaust.

Tim Adams

All Day Long by Joanna Biggs; Purity by Jonathan Franzen; John Berger on Artists

Joanna Biggs’s first book, All Day Long (Serpent’s Tail), is that rare thing, an insight into Britain with no ideological preconception. Biggs travelled the country simply asking people how they earned a living; the answers are both sobering and surprising. It has become a sport among critics to chastise Jonathan Franzen for what he is not. Better, enjoy what he is: a great comic novelist, and wonderful observer of contemporary relationships. Purity (Fourth Estate) is rickety, sometimes unbelievable, but it had me laughing – and thinking – more than any other fiction this year. The book I’d most like to receive? Portraits: John Berger on Artists (Verso).

Joanna Biggs’s first book, All Day Long (Serpent’s Tail), is that rare thing, an insight into Britain with no ideological preconception. Biggs travelled the country simply asking people how they earned a living; the answers are both sobering and surprising. It has become a sport among critics to chastise Jonathan Franzen for what he is not. Better, enjoy what he is: a great comic novelist, and wonderful observer of contemporary relationships. Purity (Fourth Estate) is rickety, sometimes unbelievable, but it had me laughing – and thinking – more than any other fiction this year. The book I’d most like to receive? Portraits: John Berger on Artists (Verso).

David Nicholls

The Green Road by Anne Enright; Limonov by Emmanuel Carrère

Anne Enright’s The Green Road (Jonathan Cape) takes a familiar story, the troubled family reunion, and makes it feel fresh and new. The second chapter, set in New York in the early 90s, is a highlight, but I loved all of this wise, funny, moving book. I was also completely gripped by Emmanuel Carrère’s Limonov (Penguin Modern Classics), a brilliantly original fusion of fiction and biography with a central character who is alternately charming and loathsome, admirable and appalling as he storms his way through postwar Russia, New York, Paris and Yugoslavia. It’s also translated with great skill and precision by John Lambert. Every word feels right. The wish list is long and includes Mary Beard’s SPQR (Profile), Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone (Canongate), Jonathan Coe’s Number 11 (Viking), Philip Hensher’s two-volume Penguin Book of the British Short Story and the works of Kent Haruf, whose posthumous novella, Our Souls at Night (Picador), was another of the year’s highlights.

Anne Enright’s The Green Road (Jonathan Cape) takes a familiar story, the troubled family reunion, and makes it feel fresh and new. The second chapter, set in New York in the early 90s, is a highlight, but I loved all of this wise, funny, moving book. I was also completely gripped by Emmanuel Carrère’s Limonov (Penguin Modern Classics), a brilliantly original fusion of fiction and biography with a central character who is alternately charming and loathsome, admirable and appalling as he storms his way through postwar Russia, New York, Paris and Yugoslavia. It’s also translated with great skill and precision by John Lambert. Every word feels right. The wish list is long and includes Mary Beard’s SPQR (Profile), Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone (Canongate), Jonathan Coe’s Number 11 (Viking), Philip Hensher’s two-volume Penguin Book of the British Short Story and the works of Kent Haruf, whose posthumous novella, Our Souls at Night (Picador), was another of the year’s highlights.

Louise Doughty

The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall; The Lives of Women by Christine Dwyer; The Death of Rex Nhongo by CB George

I’ve had the privilege of judging two fiction prizes this year, the Desmond Elliott prize for new fiction and the Costa novel award. I commend the shortlists of both – but the problem with shortlists is that they are too short, so I’d also like to say how much I enjoyed The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall (Faber), The Lives of Women by Christine Dwyer Hickey (Atlantic) and The Death of Rex Nhongo by CB George (Quercus). I’ve never read George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London (Penguin Modern Classics), a terrible admission; that would be an appropriate corrective to Christmas excess.

I’ve had the privilege of judging two fiction prizes this year, the Desmond Elliott prize for new fiction and the Costa novel award. I commend the shortlists of both – but the problem with shortlists is that they are too short, so I’d also like to say how much I enjoyed The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall (Faber), The Lives of Women by Christine Dwyer Hickey (Atlantic) and The Death of Rex Nhongo by CB George (Quercus). I’ve never read George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London (Penguin Modern Classics), a terrible admission; that would be an appropriate corrective to Christmas excess.

Lara Feigel

A Curious Friendship by Anna Thomasson; Weatherland by Alexandra Harris

This has been a great year for experiments in non-fiction. Anna Thomasson’s A Curious Friendship (Macmillan) tells the story of Rex Whistler and Edith Olivier with haunting novelistic intensity – a remarkable first book. Alexandra Harris’s brilliantly eclectic Weatherland (Thames & Hudson) has made the colours of autumnal Britain even richer than usual and I am optimistic that her portraits of literary winters across the centuries will make me more than usually disposed to Christmas cheer. This would also be aided by some more fantastical storytelling, though, so I am hoping that Christmas Day will bring a copy of Katherine Rundell’s bewitching-looking The Wolf Wilder (Bloomsbury) to read to my son on dark evenings.

This has been a great year for experiments in non-fiction. Anna Thomasson’s A Curious Friendship (Macmillan) tells the story of Rex Whistler and Edith Olivier with haunting novelistic intensity – a remarkable first book. Alexandra Harris’s brilliantly eclectic Weatherland (Thames & Hudson) has made the colours of autumnal Britain even richer than usual and I am optimistic that her portraits of literary winters across the centuries will make me more than usually disposed to Christmas cheer. This would also be aided by some more fantastical storytelling, though, so I am hoping that Christmas Day will bring a copy of Katherine Rundell’s bewitching-looking The Wolf Wilder (Bloomsbury) to read to my son on dark evenings.

Kirsty Wark

A Woman’s War by Lee Miller; A Year of Good Eating by Nigel Slater

Both my choices this year are non-fiction. The fiction “to read” pile stands like a wonky tower looming over my bed – but the rewards of these two books are immense. Lee Miller: A Woman’s War (Thames & Hudson) is proof that the photograph is often more powerful and intense than the moving image. Each minute spent studying Miller’s absorbing shots of the liberation delivers a new detail and perhaps because my father was in France and then Germany, they help me to understand what he really saw. I must sound like a broken record, but Nigel Slater’s books are as consistently good as his food. A Year of Good Eating (Fourth Estate) is the real way to cook. It forces me to take my time and read his engaging prose before I put on my apron and deliver such delights as “a surprising whiff of orange blossom”.

Both my choices this year are non-fiction. The fiction “to read” pile stands like a wonky tower looming over my bed – but the rewards of these two books are immense. Lee Miller: A Woman’s War (Thames & Hudson) is proof that the photograph is often more powerful and intense than the moving image. Each minute spent studying Miller’s absorbing shots of the liberation delivers a new detail and perhaps because my father was in France and then Germany, they help me to understand what he really saw. I must sound like a broken record, but Nigel Slater’s books are as consistently good as his food. A Year of Good Eating (Fourth Estate) is the real way to cook. It forces me to take my time and read his engaging prose before I put on my apron and deliver such delights as “a surprising whiff of orange blossom”.

Alison Light

An Impatient Life by Daniel Bensaid; A Notable Woman by Jean Lucey Pratt

Two utterly different testaments: Daniel Bensaid’s engrossing and inspiring An Impatient Life (Verso), his reflections on politics, philosophy and activism on the militant French left; and A Notable Woman: The Romantic Journals of Jean Lucey Pratt (Canongate), recording the author’s moods, ambitions and “amorous adventures” across 60 years in the home counties – exasperating, funny and poignant. I’d like Thomas W Laqueur’s The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains (Princeton University Press) as a vade mecum for 2016.

Two utterly different testaments: Daniel Bensaid’s engrossing and inspiring An Impatient Life (Verso), his reflections on politics, philosophy and activism on the militant French left; and A Notable Woman: The Romantic Journals of Jean Lucey Pratt (Canongate), recording the author’s moods, ambitions and “amorous adventures” across 60 years in the home counties – exasperating, funny and poignant. I’d like Thomas W Laqueur’s The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains (Princeton University Press) as a vade mecum for 2016.

David Kynaston

The Railways by Simon Bradley; Promised You a Miracle by Andy Beckett

Simon Bradley’s The Railways (Profile) is an astonishing 3D recreation of the British railway experience over the past two centuries: a classic. As the present government turns daily to the early 80s playbook, Andy Beckett’s Promised You a Miracle (Allen Lane), a rich survey of those troubled years, could not be more timely. Most innovative, if uncomfortable, is his teasing out of what he calls “secret Thatcherites”, which included many readers of this paper. For Christmas, please, Clive James’s Latest Readings (Yale).

Simon Bradley’s The Railways (Profile) is an astonishing 3D recreation of the British railway experience over the past two centuries: a classic. As the present government turns daily to the early 80s playbook, Andy Beckett’s Promised You a Miracle (Allen Lane), a rich survey of those troubled years, could not be more timely. Most innovative, if uncomfortable, is his teasing out of what he calls “secret Thatcherites”, which included many readers of this paper. For Christmas, please, Clive James’s Latest Readings (Yale).

Colm Tóibín

1606: Shakespeare and the Year of Lear by James Shapiro; Tender by Belinda McKeon; I Must Be Living Twice by Eileen Myles

James Shapiro’s 1606: Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (Faber) is a meticulous narrative of a momentous year in the life of the playwright and a masterpiece of intelligent literary criticism. Belinda McKeon’s Tender (Picador) captures what it is like to be young in Dublin with grace, subtlety and sympathy. She makes her characters both alluring and complex, and indeed dangerous, too. Eileen Myles’s I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems (Ecco Press) are engaging, filled with urgent, personal tones, steeped in the street life of New York.

James Shapiro’s 1606: Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (Faber) is a meticulous narrative of a momentous year in the life of the playwright and a masterpiece of intelligent literary criticism. Belinda McKeon’s Tender (Picador) captures what it is like to be young in Dublin with grace, subtlety and sympathy. She makes her characters both alluring and complex, and indeed dangerous, too. Eileen Myles’s I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems (Ecco Press) are engaging, filled with urgent, personal tones, steeped in the street life of New York.

Tim Dee

The Cabaret of Plants by Richard Mabey; Weatherland by Alexandra Harris

Nobody, it seems, wants now to be called a “nature writer” but two excellent natural histories made clever play with the poetry of outdoor facts this year. Richard Mabey’s The Cabaret of Plants (Profile), about humankind’s attempts to cotton on to the vegetable world, is wonderfully seedy. Alexandra Harris’s Weatherland (Thames & Hudson) proves that while no one needs a weatherman to know which way the wind blows the assorted creatives of England have long made climate tell. And one wanted, since it’s not dark yet: a history of twilight – Peter Davidson’s The Last of the Light (Reaktion)

Nobody, it seems, wants now to be called a “nature writer” but two excellent natural histories made clever play with the poetry of outdoor facts this year. Richard Mabey’s The Cabaret of Plants (Profile), about humankind’s attempts to cotton on to the vegetable world, is wonderfully seedy. Alexandra Harris’s Weatherland (Thames & Hudson) proves that while no one needs a weatherman to know which way the wind blows the assorted creatives of England have long made climate tell. And one wanted, since it’s not dark yet: a history of twilight – Peter Davidson’s The Last of the Light (Reaktion)

Ali Smith

A Woman on the Edge of Time by Jeremy Gavron; We Don't Know What We're Doing by Thomas Morris

I was mesmerised by Jeremy Gavron’s extraordinary memoir of his mother, Hannah Gavron, A Woman on the Edge of Time (Scribe). It’s one of those works that cross over into the real life so justly that all of life is better understood by it, and what books can do with lives – and vice versa, what lives can do with books – is enhanced by it. Then there’s Thomas Morris’s We Don’t Know What We’re Doing (Faber), a debut collection of short stories, heart-hurtingly acute, laugh-out-loud funny, and not just a book of the year for me but one of the most satisfying collections I’ve read for years. And all I want for Christmas is The Collected Poems & Drawings of Stevie Smith, edited by Will May (Faber). That’ll melt a path through midwinter.

I was mesmerised by Jeremy Gavron’s extraordinary memoir of his mother, Hannah Gavron, A Woman on the Edge of Time (Scribe). It’s one of those works that cross over into the real life so justly that all of life is better understood by it, and what books can do with lives – and vice versa, what lives can do with books – is enhanced by it. Then there’s Thomas Morris’s We Don’t Know What We’re Doing (Faber), a debut collection of short stories, heart-hurtingly acute, laugh-out-loud funny, and not just a book of the year for me but one of the most satisfying collections I’ve read for years. And all I want for Christmas is The Collected Poems & Drawings of Stevie Smith, edited by Will May (Faber). That’ll melt a path through midwinter.

Maria Popova

Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs by Lisa Randall; Enormous Smallness by Matthew Burgess

In Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs (Bodley Head), Harvard particle physicist and cosmologist Lisa Randall, one of the sharpest scientific minds of our time, presents a fascinating speculative theory linking the extinction of the dinosaurs to dark matter. Undergirding the theory is an insightful exploration of larger questions about the history of the universe, the lineage of scientific breakthroughs, the trials and triumphs of life on Earth, and the incubation period of consequences. Beloved poet EE Cummings (who, contrary to popular misconception, signed his name both in all lower case and properly capitalised) remains one of the most innovative creative voices of the 20th century. Enormous Smallness by Matthew Burgess, with illustrations by Kris Di Giacomo, is a lyrical illustrated biography that chronicles his life and creative bravery with uncommon tenderness, befitting Cummings’s one-time proclamation that he is “an author of pictures, a draughtsman of words”. On my wishlist is Lord Byron’s Don Juan, annotated by Isaac Asimov and illustrated by Milton Glaser (Doubleday).

In Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs (Bodley Head), Harvard particle physicist and cosmologist Lisa Randall, one of the sharpest scientific minds of our time, presents a fascinating speculative theory linking the extinction of the dinosaurs to dark matter. Undergirding the theory is an insightful exploration of larger questions about the history of the universe, the lineage of scientific breakthroughs, the trials and triumphs of life on Earth, and the incubation period of consequences. Beloved poet EE Cummings (who, contrary to popular misconception, signed his name both in all lower case and properly capitalised) remains one of the most innovative creative voices of the 20th century. Enormous Smallness by Matthew Burgess, with illustrations by Kris Di Giacomo, is a lyrical illustrated biography that chronicles his life and creative bravery with uncommon tenderness, befitting Cummings’s one-time proclamation that he is “an author of pictures, a draughtsman of words”. On my wishlist is Lord Byron’s Don Juan, annotated by Isaac Asimov and illustrated by Milton Glaser (Doubleday).

Melvyn Bragg

R.I.P. by Nigel Williams; Genghis Khan by Frank McLynn; The Next Review

R.I.P. by Nigel Williams (Corsair Books): this is Williams at his best. Wonderfully funny from slapstick to satire to sly suburban comedy, all in a weirdly convincing story told by a dead man. A virtuoso performance. Genghis Khan: The Man Who Conquered the World by Frank McLynn (Bodley Head): this powerful and comprehensive study of the great Mongol takes your breath away with the sheer scale and fury of the man’s conquests and cruelties. Told with chilling relish. The Next Review, edited by Patrick Davidson Roberts (by subscription): rooted in Ian Hamilton’s editorship of the New Review, Davidson Roberts sails into (mainly) contemporary poetry, and convincingly takes up Hamilton’s banner. The books that I would like to be given for Christmas are The Poems of TS Eliot: Volume 1 and 2 edited by Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue (Faber ).

R.I.P. by Nigel Williams (Corsair Books): this is Williams at his best. Wonderfully funny from slapstick to satire to sly suburban comedy, all in a weirdly convincing story told by a dead man. A virtuoso performance. Genghis Khan: The Man Who Conquered the World by Frank McLynn (Bodley Head): this powerful and comprehensive study of the great Mongol takes your breath away with the sheer scale and fury of the man’s conquests and cruelties. Told with chilling relish. The Next Review, edited by Patrick Davidson Roberts (by subscription): rooted in Ian Hamilton’s editorship of the New Review, Davidson Roberts sails into (mainly) contemporary poetry, and convincingly takes up Hamilton’s banner. The books that I would like to be given for Christmas are The Poems of TS Eliot: Volume 1 and 2 edited by Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue (Faber ).

Matt Haig

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari; All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

I was a bit behind the curve on Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Vintage) by Yuval Noah Harari. It’s one of those books that contains a remarkable piece of information on almost every page and reminds us that we should be grateful to be human. Fiction-wise, Costa-prize judging kept me busy but I was mesmerised by Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See (Fourth Estate), which is sprawling and weird and beautiful. And the book I’d most like from Father Christmas is Mary Beard’s SPQR (Profile), as I am an ancient Rome geek and it looks spectacular.

I was a bit behind the curve on Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Vintage) by Yuval Noah Harari. It’s one of those books that contains a remarkable piece of information on almost every page and reminds us that we should be grateful to be human. Fiction-wise, Costa-prize judging kept me busy but I was mesmerised by Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See (Fourth Estate), which is sprawling and weird and beautiful. And the book I’d most like from Father Christmas is Mary Beard’s SPQR (Profile), as I am an ancient Rome geek and it looks spectacular.

Rachel Cooke

The Past by Tessa Hadley; Number 11 by Jonathan Coe; A Woman on the Edge of Time by Jeremy Gavron

The best novels I read this year were Tessa Hadley’s The Past (Jonathan Cape) – no one delineates familial bad behaviour the way she does – and Number 11 (Viking), Jonathan Coe’s savage, tender-hearted and crazily enjoyable portrait of 21st-century Britain, which might as well have been superglued to my hands for all that I was able to put it down. (It comes complete with a reality TV show and a haunted super-basement.) And I want everyone to read Jeremy Gavron’s memoir, A Woman on the Edge of Time (Scribe), about the suicide of his mother, Hannah, in 1965. The book I’d most like to find under the tree – oh, please, let those mournful goggle eyes be looking out at me come Christmas morning – is Richard Bradford’s The Importance of Elsewhere: Philip Larkin’s Photographs (Frances Lincoln).

The best novels I read this year were Tessa Hadley’s The Past (Jonathan Cape) – no one delineates familial bad behaviour the way she does – and Number 11 (Viking), Jonathan Coe’s savage, tender-hearted and crazily enjoyable portrait of 21st-century Britain, which might as well have been superglued to my hands for all that I was able to put it down. (It comes complete with a reality TV show and a haunted super-basement.) And I want everyone to read Jeremy Gavron’s memoir, A Woman on the Edge of Time (Scribe), about the suicide of his mother, Hannah, in 1965. The book I’d most like to find under the tree – oh, please, let those mournful goggle eyes be looking out at me come Christmas morning – is Richard Bradford’s The Importance of Elsewhere: Philip Larkin’s Photographs (Frances Lincoln).

Marina Warner

Subtly Worded by Teffi; Leg Over Leg by Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq; The Astronomer and the Witch by Ulinka Rublack

Teffi is one of those writers who can speak of dreadful things and make you laugh out loud. Subtly Worded (Pushkin Press) is a collection of her wonderfully observant, succinct and witty stories, written in Russia before the revolution and in Paris till her death in 1952, most effectively translated by Anne-Marie Jackson, Robert Chandler and others. Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq’s Leg Over Leg, first published in Paris in Arabic in 1855, now dazzlingly translated into English for the first time by Humphrey Davies, is out in paperback (New York University Press). At times scabrous, at times melancholy, this inquiry into sex, belief, foreign countries and their ways should tilt the view of 19th-century fiction. In The Astronomer and the Witch (Oxford University Press), Ulinka Rublack shows wonderful sensitivity about mothers, old age, and female struggles, as she unpicks the trial of Johannes Kepler’s mother for witchcraft. Finally, I want to read In Search of the Christian Buddha: How an Asian Sage Became a Medieval Saint (Norton), by Donald S Lopez and Peggy McCracken, who, as they trace the migration of a figure through different cultures, examine the vitality of stories.

Teffi is one of those writers who can speak of dreadful things and make you laugh out loud. Subtly Worded (Pushkin Press) is a collection of her wonderfully observant, succinct and witty stories, written in Russia before the revolution and in Paris till her death in 1952, most effectively translated by Anne-Marie Jackson, Robert Chandler and others. Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq’s Leg Over Leg, first published in Paris in Arabic in 1855, now dazzlingly translated into English for the first time by Humphrey Davies, is out in paperback (New York University Press). At times scabrous, at times melancholy, this inquiry into sex, belief, foreign countries and their ways should tilt the view of 19th-century fiction. In The Astronomer and the Witch (Oxford University Press), Ulinka Rublack shows wonderful sensitivity about mothers, old age, and female struggles, as she unpicks the trial of Johannes Kepler’s mother for witchcraft. Finally, I want to read In Search of the Christian Buddha: How an Asian Sage Became a Medieval Saint (Norton), by Donald S Lopez and Peggy McCracken, who, as they trace the migration of a figure through different cultures, examine the vitality of stories.

Stephanie Merritt

The Kindness by Polly Samson; 1606 by James Shapiro; M Train by Patti Smith

My novel of the year is Polly Samson’s The Kindness (Bloomsbury): a moving family drama, beautifully written, with twists engineered like a thriller. James Shapiro’s 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (Faber) is a superb follow-up to his 1599, packed with intriguing discoveries that bring the Jacobean world to life. For Christmas I’ve asked for M Train, the new memoir by Patti Smith (Bloomsbury) – she’s always been a heroine and her voice is just as original in her prose as in her songs.

My novel of the year is Polly Samson’s The Kindness (Bloomsbury): a moving family drama, beautifully written, with twists engineered like a thriller. James Shapiro’s 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (Faber) is a superb follow-up to his 1599, packed with intriguing discoveries that bring the Jacobean world to life. For Christmas I’ve asked for M Train, the new memoir by Patti Smith (Bloomsbury) – she’s always been a heroine and her voice is just as original in her prose as in her songs.

Jackie Kay

Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine; How to Be Both by Ali Smith; 40 Sonnets by Don Paterson

Ali Smith’s How to Be Both (Penguin) leaps across time and space and is a searing exploration of teenage bereavement as well as a true celebration of life; Don Paterson finds more room in the sonnet than you’d find in some novels and strides through the ages, marrying craft to grain in 40 Sonnets (Faber). Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (Penguin) is a Whitmanesque song to the self and a vigorous yet witty exploration of racism across the jugulars of time. Each book I’ve loved has done something startling with the form and made me think all the time about time. I’d like to be given Jeremy Gavron’s memoir, A Woman on the Edge of Time (Scribe). The short extract I read struck a chord: the way that absence can become a strong presence in our lives.

Ali Smith’s How to Be Both (Penguin) leaps across time and space and is a searing exploration of teenage bereavement as well as a true celebration of life; Don Paterson finds more room in the sonnet than you’d find in some novels and strides through the ages, marrying craft to grain in 40 Sonnets (Faber). Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (Penguin) is a Whitmanesque song to the self and a vigorous yet witty exploration of racism across the jugulars of time. Each book I’ve loved has done something startling with the form and made me think all the time about time. I’d like to be given Jeremy Gavron’s memoir, A Woman on the Edge of Time (Scribe). The short extract I read struck a chord: the way that absence can become a strong presence in our lives.

Niall Ferguson

The Maisky Diaries edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky; The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

The day I finished the first volume of the biography I’ve been toiling over, I went to a bookshop to give myself a reward: Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel, The Buried Giant (Faber). I was mesmerised. I have been in some measure spellbound by everything Ishiguro has written, but this new book was like a doorway into a magical world, half strange and half familiar. It is England in the dark ages. An elderly couple are seeking their long-lost son. But their thoughts and memories seem somehow damaged and incomplete. The magical and the real coexist disconcertingly. The achievement is remarkable. Is it just old age that has addled their minds? Or is it sorcery? There is also a giant in The Maisky Diaries (Yale), superbly edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky. The giant is Churchill, whom we see from an entirely new and revealing viewpoint: that of the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky. It is September 1938, and Churchill is entertaining Maisky at Chartwell. “In my cellar I have a bottle of wine from 1793,” declares Churchill. “I’m keeping it for a very special, truly exceptional occasion.” “Which, exactly, may I ask you?” asks Maisky. Churchill “grinned cunningly, paused, then suddenly declared: ‘We’ll drink this bottle together when Great Britain and Russia beat Hitler’s Germany!’”

The day I finished the first volume of the biography I’ve been toiling over, I went to a bookshop to give myself a reward: Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel, The Buried Giant (Faber). I was mesmerised. I have been in some measure spellbound by everything Ishiguro has written, but this new book was like a doorway into a magical world, half strange and half familiar. It is England in the dark ages. An elderly couple are seeking their long-lost son. But their thoughts and memories seem somehow damaged and incomplete. The magical and the real coexist disconcertingly. The achievement is remarkable. Is it just old age that has addled their minds? Or is it sorcery? There is also a giant in The Maisky Diaries (Yale), superbly edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky. The giant is Churchill, whom we see from an entirely new and revealing viewpoint: that of the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky. It is September 1938, and Churchill is entertaining Maisky at Chartwell. “In my cellar I have a bottle of wine from 1793,” declares Churchill. “I’m keeping it for a very special, truly exceptional occasion.” “Which, exactly, may I ask you?” asks Maisky. Churchill “grinned cunningly, paused, then suddenly declared: ‘We’ll drink this bottle together when Great Britain and Russia beat Hitler’s Germany!’”

Joe Dunthorne

The Wallcreeper by Nell Zink; Citizen by Claudia Rankine

I loved Nell Zink’s energetic and unsentimental The Wallcreeper (Fourth Estate), which announces itself from the first line: “I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage.” I can’t imagine the word “occasioned” has ever worked so hard. I was also hypnotised by Claudia Rankine’s brilliant and terrifying Citizen (Penguin). For Christmas, I’d like someone to exquisitely translate then beautifully publish then give me the novels of Wang Xiaobo, a great Chinese writer who has only a few stories and novellas in English.

I loved Nell Zink’s energetic and unsentimental The Wallcreeper (Fourth Estate), which announces itself from the first line: “I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage.” I can’t imagine the word “occasioned” has ever worked so hard. I was also hypnotised by Claudia Rankine’s brilliant and terrifying Citizen (Penguin). For Christmas, I’d like someone to exquisitely translate then beautifully publish then give me the novels of Wang Xiaobo, a great Chinese writer who has only a few stories and novellas in English.

Geoff Dyer

The Visiting Privilege by Joy Williams

Joy Williams’s The Visiting Privilege (Knopf) is 500 pages – and more than four decades – of uncut genius. Her world is recognisably ordinary and thoroughly weird, full of busted hopes and solace so wayward it might be a source of further torment – or just more hilarity. The stories are often borderline deranged – then they cross the border. I hope someone will give me Sally Mann's “memoir with photographs” Hold Still (Little, Brown).

Joy Williams’s The Visiting Privilege (Knopf) is 500 pages – and more than four decades – of uncut genius. Her world is recognisably ordinary and thoroughly weird, full of busted hopes and solace so wayward it might be a source of further torment – or just more hilarity. The stories are often borderline deranged – then they cross the border. I hope someone will give me Sally Mann's “memoir with photographs” Hold Still (Little, Brown).

Helen Dunmore

Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman; Waiting for the Past by Les Murray

Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman (Viking) is a subtle, measured biography, full of insight into Brontë’s fiery intellect as well as the tragic intensity of her experience. Harman is especially good on the period Brontë spent as a pupil and teacher in Brussels and on her transformative relationship with Professor Constantin Héger. Les Murray's Waiting for the Past (Carcanet) – no one writes like Murray: so truthful, nakedly emotional, wry, watchful. He’s set deep in the Australian landscape, writing about back roads, vertigo, sliced bread, old typewriters and the persistence of love. Murray is the holy fool of his own poems, and a hero of poetry. For Christmas, I’d like James Attlee’s Station to Station, Searching for Stories on the Great Western Line (Guardian Books).

Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman (Viking) is a subtle, measured biography, full of insight into Brontë’s fiery intellect as well as the tragic intensity of her experience. Harman is especially good on the period Brontë spent as a pupil and teacher in Brussels and on her transformative relationship with Professor Constantin Héger. Les Murray's Waiting for the Past (Carcanet) – no one writes like Murray: so truthful, nakedly emotional, wry, watchful. He’s set deep in the Australian landscape, writing about back roads, vertigo, sliced bread, old typewriters and the persistence of love. Murray is the holy fool of his own poems, and a hero of poetry. For Christmas, I’d like James Attlee’s Station to Station, Searching for Stories on the Great Western Line (Guardian Books).

Stuart Evers

Nocilla Dream by Agustín Fernández Mallo; Karate Chop by Dorthe Nor; Imaginary Cities by Darran Anderson

Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone (Canongate) is the most surprising, bold and instantly memorable novel I read this year: a fiction of sustained and sometimes terrifying genius. Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Nocilla Dream (Fitzcarraldo Editions) is a breathtaking work of innovation and heart. Dorthe Nors’s Karate Chop (Pushkin Press) is an unsettling delight, while Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities (Influx Press) is a dizzying and brilliant piece of creative non-fiction. For Christmas, I’m hoping for the much-praised The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli (Granta).

Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone (Canongate) is the most surprising, bold and instantly memorable novel I read this year: a fiction of sustained and sometimes terrifying genius. Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Nocilla Dream (Fitzcarraldo Editions) is a breathtaking work of innovation and heart. Dorthe Nors’s Karate Chop (Pushkin Press) is an unsettling delight, while Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities (Influx Press) is a dizzying and brilliant piece of creative non-fiction. For Christmas, I’m hoping for the much-praised The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli (Granta).

Rachel Joyce

The Iceberg by Marion Coutts; A Spool of Blue Thread by Anne Tyler; A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

I read A Spool of Blue Thread (Chatto & Windus) in January and it remains one of my favourites. Anne Tyler takes the ordinary, the small, and makes them sing. I loved Keeping an Eye Open (Jonathan Cape), Julian Barnes’s collection of essays on art; thought-provoking, beautifully presented, tender. And finally, Marion Coutts’s blazing memoir The Iceberg (Atlantic), which came out in paperback this year, hit me like a train. I would like A Little Life (Picador) by Hanya Yanagihara for Christmas, though I suspect it will wreck more than my felt stocking. So please can I have a book with pictures as well? The Magpie & the Wardrobe by Sam McKechnie and Alexandrine Portelli (Pavilion) should do it.

I read A Spool of Blue Thread (Chatto & Windus) in January and it remains one of my favourites. Anne Tyler takes the ordinary, the small, and makes them sing. I loved Keeping an Eye Open (Jonathan Cape), Julian Barnes’s collection of essays on art; thought-provoking, beautifully presented, tender. And finally, Marion Coutts’s blazing memoir The Iceberg (Atlantic), which came out in paperback this year, hit me like a train. I would like A Little Life (Picador) by Hanya Yanagihara for Christmas, though I suspect it will wreck more than my felt stocking. So please can I have a book with pictures as well? The Magpie & the Wardrobe by Sam McKechnie and Alexandrine Portelli (Pavilion) should do it.

Hari Kunzru

Points of Origin by Diao Dou; The Wake by Paul Kingsnorth; The Planet Remade by Oliver Morton

I enjoyed Points of Origin, a collection by the Chinese satirist Diao Dou (Comma Press), an absurdist portrait of life during the Cultural Revolution and after. Paul Kingsnorth’s The Wake (Unbound), set in the aftermath of the Norman invasion of England, is written in a quasi-Anglo Saxon dialect. I admired Oliver Morton’s book about geo-engineering, The Planet Remade (Granta), which tries to think through what’s technologically possible to do about climate change. For Christmas, I’d like enough time to myself to read at least some of Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon (Princeton University Press).

I enjoyed Points of Origin, a collection by the Chinese satirist Diao Dou (Comma Press), an absurdist portrait of life during the Cultural Revolution and after. Paul Kingsnorth’s The Wake (Unbound), set in the aftermath of the Norman invasion of England, is written in a quasi-Anglo Saxon dialect. I admired Oliver Morton’s book about geo-engineering, The Planet Remade (Granta), which tries to think through what’s technologically possible to do about climate change. For Christmas, I’d like enough time to myself to read at least some of Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon (Princeton University Press).

Frank Cottrell Boyce

The Givenness of Things by Marilynne Robinson; My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante; Debt by David Graeber

The most engrossing book I read this year was The Givenness of Things (Virago), Marilynne Robinson’s celebration of the irreducible complexity of human beings. I was addicted to Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (Europa Editions). The wonder of great writing is that it uncovers our common humanity. So this northern middle-aged male found himself identifying with two teenage Neapolitan girls. I’m hoping that someone will give me the sequels for Christmas. Everyone needs to read David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years (Melville House) because it’s all true.

The most engrossing book I read this year was The Givenness of Things (Virago), Marilynne Robinson’s celebration of the irreducible complexity of human beings. I was addicted to Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (Europa Editions). The wonder of great writing is that it uncovers our common humanity. So this northern middle-aged male found himself identifying with two teenage Neapolitan girls. I’m hoping that someone will give me the sequels for Christmas. Everyone needs to read David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years (Melville House) because it’s all true.

Hanya Yanagihara

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro; A Spool of Blue Thread by Anne Tyler; The Way Things Were by Aatish Taseer

The list of what I haven’t read this year (yet) is too embarrassing to detail – especially as it includes a work by one of the writers I admire most, The Blue Guitar by John Banville (Viking). At least I read books by two of my other favourite writers. Months later, I’m still thinking about Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant (Faber): its unsettling set pieces, its looping narrative, its eerie and beautiful images, how remarkably and totally it enchants and discomfits. And I have long loved Anne Tyler’s work: as a writer, it’s so difficult to create a world that’s completely, inimitably yours. But when you read A Spool of Blue Thread (Chatto & Windus), you’re reminded that even Tyler’s sentences are wholly hers, instantly recognisable and impossible to duplicate. I also very much enjoyed Aatish Taseer’s The Way Things Were (Picador), in particular how precisely, and stingingly, he records scenes of upper-class Indian society. I’m looking forward to reading Eka Kurniawan’s epic Beauty Is a Wound (New Directions) and would also love Portraits: John Berger on Artists (Verso).

The list of what I haven’t read this year (yet) is too embarrassing to detail – especially as it includes a work by one of the writers I admire most, The Blue Guitar by John Banville (Viking). At least I read books by two of my other favourite writers. Months later, I’m still thinking about Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant (Faber): its unsettling set pieces, its looping narrative, its eerie and beautiful images, how remarkably and totally it enchants and discomfits. And I have long loved Anne Tyler’s work: as a writer, it’s so difficult to create a world that’s completely, inimitably yours. But when you read A Spool of Blue Thread (Chatto & Windus), you’re reminded that even Tyler’s sentences are wholly hers, instantly recognisable and impossible to duplicate. I also very much enjoyed Aatish Taseer’s The Way Things Were (Picador), in particular how precisely, and stingingly, he records scenes of upper-class Indian society. I’m looking forward to reading Eka Kurniawan’s epic Beauty Is a Wound (New Directions) and would also love Portraits: John Berger on Artists (Verso).

Nicci Gerrard

On Elizabeth Bishop by Colm Tóibín; Stammered Songbook by Erwin Mortimer; Dept of Speculation by Jenny Offill

I loved Colm Tóibín’s On Elizabeth Bishop (Princeton University Press): it helped me read this mysterious, often withholding poet, and is like a conversation across the decades between two great writers. Stammered Songbook by Erwin Mortier (Pushkin Press) is a remarkable meditation on dementia and the nature of identity, as the Belgian poet watches his mother being vandalised and destroyed by the disease. It’s a struggle to give words to what is wordless, painful but also astonishingly beautiful. And because it was published in paperback this year, I can sneak in the slender, heart-wrenching essence-of-a-novel by Jenny Offill, Dept. of Speculation (Granta). Romance, marriage, motherhood and then abandonment are told through fragments, proverbs, scientific facts, all deftly gathered into the shape of a life rushing by, in which me and you become she and him.

I loved Colm Tóibín’s On Elizabeth Bishop (Princeton University Press): it helped me read this mysterious, often withholding poet, and is like a conversation across the decades between two great writers. Stammered Songbook by Erwin Mortier (Pushkin Press) is a remarkable meditation on dementia and the nature of identity, as the Belgian poet watches his mother being vandalised and destroyed by the disease. It’s a struggle to give words to what is wordless, painful but also astonishingly beautiful. And because it was published in paperback this year, I can sneak in the slender, heart-wrenching essence-of-a-novel by Jenny Offill, Dept. of Speculation (Granta). Romance, marriage, motherhood and then abandonment are told through fragments, proverbs, scientific facts, all deftly gathered into the shape of a life rushing by, in which me and you become she and him.

Robert McCrum

Katherine Carlyle by Rupert Thomson; Every Time a Friend Succeeds Something Inside Me Dies by Jay Parini

My novel of the year is Rupert Thomson’s haunting family tale, Katherine Carlyle (Little, Brown), a contemporary masterpiece. In a good year for biography, the life I enjoyed the most, a gossipy window on a great American, is Jay Parini’s life of Gore Vidal, Every Time a Friend Succeeds Something Inside Me Dies (Little, Brown). Benjamin Taylor’s Proust: The Search (Yale) is a miracle of brevity and brilliance. For macabre fascination, I’d like a copy of Charles Saatchi’s Dead (Booth-Clibborn).

My novel of the year is Rupert Thomson’s haunting family tale, Katherine Carlyle (Little, Brown), a contemporary masterpiece. In a good year for biography, the life I enjoyed the most, a gossipy window on a great American, is Jay Parini’s life of Gore Vidal, Every Time a Friend Succeeds Something Inside Me Dies (Little, Brown). Benjamin Taylor’s Proust: The Search (Yale) is a miracle of brevity and brilliance. For macabre fascination, I’d like a copy of Charles Saatchi’s Dead (Booth-Clibborn).

Curtis Sittenfeld

Make Your Home Among Strangers by Jennine Capó Crucet; A Big Enough Lie by Eric Bennett

My favourite books of 2015 were two excellent first novels. Make Your Home Among Strangers (St Martin’s Press) by Jennine Capó Crucet is about a Cuban-American girl who’s the first in her family to go to college, enrolling in an elite university where she feels out of place in devastating, funny and altogether riveting ways. A Big Enough Lie (Triquarterly Books) by Eric Bennett is about a young man who writes a fake memoir of his military service in Iraq – meaning the novel is awash in deceit, vanity, literature, war and heartache. For Christmas, I’d be overjoyed to receive a copy of Strangers Drowning (Allen Lane) by Larissa MacFarquhar, which apparently is non-fiction about “extreme do-gooders” and sounds fascinating.

My favourite books of 2015 were two excellent first novels. Make Your Home Among Strangers (St Martin’s Press) by Jennine Capó Crucet is about a Cuban-American girl who’s the first in her family to go to college, enrolling in an elite university where she feels out of place in devastating, funny and altogether riveting ways. A Big Enough Lie (Triquarterly Books) by Eric Bennett is about a young man who writes a fake memoir of his military service in Iraq – meaning the novel is awash in deceit, vanity, literature, war and heartache. For Christmas, I’d be overjoyed to receive a copy of Strangers Drowning (Allen Lane) by Larissa MacFarquhar, which apparently is non-fiction about “extreme do-gooders” and sounds fascinating.

Naomi Alderman

Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel; So You've Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson

I loved Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel (Picador) – a leftwing post-apocalyptic story in which the future needs a travelling symphony as much as bullets or inexplicable insta-cannibalism. Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (Picador) is an important start to a necessary conversation on internet hate mobs. This year I’ve been rereading Oliver Sacks’s wise and humane science writing, realising how he shaped my ideas about mental health. I’d love to receive a copy of his memoir, On the Move (Picador).

I loved Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel (Picador) – a leftwing post-apocalyptic story in which the future needs a travelling symphony as much as bullets or inexplicable insta-cannibalism. Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (Picador) is an important start to a necessary conversation on internet hate mobs. This year I’ve been rereading Oliver Sacks’s wise and humane science writing, realising how he shaped my ideas about mental health. I’d love to receive a copy of his memoir, On the Move (Picador).

Alex Preston

High Dive by Jonathan Lee; The Seed Collectors by Scarlett Thomas; Dynasty by Tom Holland

Jonathan Lee’s High Dive (William Heinemann) did for the Brighton bombings what Garth Risk Hallberg’s overhyped City on Fire (Vintage) attempted to do for the New York City blackout - it’s a multivoiced epic that builds towards a stunning finale. I loved it. I also thought Scarlett Thomas’s The Seed Collectors (Canongate) a glorious, enchanting novel of ideas. Away from fiction, Tom Holland’s Dynasty (Little, Brown) was brilliant, terrifying and compelling. I was on holiday when Evie Wyld’s shark memoir, Everything Is Teeth (Jonathan Cape), illustrated by Joe Sumner, came out. Here’s hoping Father Christmas is an Observer reader and buys it for me.

Jonathan Lee’s High Dive (William Heinemann) did for the Brighton bombings what Garth Risk Hallberg’s overhyped City on Fire (Vintage) attempted to do for the New York City blackout - it’s a multivoiced epic that builds towards a stunning finale. I loved it. I also thought Scarlett Thomas’s The Seed Collectors (Canongate) a glorious, enchanting novel of ideas. Away from fiction, Tom Holland’s Dynasty (Little, Brown) was brilliant, terrifying and compelling. I was on holiday when Evie Wyld’s shark memoir, Everything Is Teeth (Jonathan Cape), illustrated by Joe Sumner, came out. Here’s hoping Father Christmas is an Observer reader and buys it for me.

Justin Webb

All the Truth is Out by Matt Bai; The World Before Us by Aislinn Hunter

My book of the year is All the Truth is Out by Matt Bai (Vintage). It’s a retelling of the story of the sex scandal disaster that befell the Democratic presidential hopeful Gary Hart, who, if he had been nominated and won in 1988, would have beaten George Bush senior and thus changed the course of history. I also loved the intensity and poetry of the novel The World Before Us by Aislinn Hunter (Hamish Hamilton). My Christmas gift: Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant (Faber).

My book of the year is All the Truth is Out by Matt Bai (Vintage). It’s a retelling of the story of the sex scandal disaster that befell the Democratic presidential hopeful Gary Hart, who, if he had been nominated and won in 1988, would have beaten George Bush senior and thus changed the course of history. I also loved the intensity and poetry of the novel The World Before Us by Aislinn Hunter (Hamish Hamilton). My Christmas gift: Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant (Faber).

Susannah Clapp

Dancing on the Outskirts by Shena Mackay; The Past by Tessa Hadley

Shena Mackay’s radiant short stories are skewering, funny and utterly original. Dancing on the Outskirts (Virago), a selection drawn from more than five decades of writing, was a high point of the year. Tessa Hadley’s The Past (Jonathan Cape) is full of wonders, not least its extraordinary, inward recreation of a child’s imagination. I would like everything in Chichester’s terrific Pallant House Gallery bookshop but will settle for Evelyn Dunbar: The Lost Works (Liss Llewellyn Fine Art), Sacha Llewellyn and Paul Liss’s catalogue of the revelatory Dunbar exhibition.

Shena Mackay’s radiant short stories are skewering, funny and utterly original. Dancing on the Outskirts (Virago), a selection drawn from more than five decades of writing, was a high point of the year. Tessa Hadley’s The Past (Jonathan Cape) is full of wonders, not least its extraordinary, inward recreation of a child’s imagination. I would like everything in Chichester’s terrific Pallant House Gallery bookshop but will settle for Evelyn Dunbar: The Lost Works (Liss Llewellyn Fine Art), Sacha Llewellyn and Paul Liss’s catalogue of the revelatory Dunbar exhibition.

Justin Cartwright

Us Conductors by Sean Michaels; All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews; The Forgiven by Lawrence Osborne

Us Conductors by Sean Michaels (Bloomsbury) won the Canadian Giller prize last year and is now published in Britain. It is a wonderful book, based on a true story of a Russian spy who lived in New York for some years between the wars, making a musical reputation while he was there as a pioneer of the theremin. His story is so extraordinary and so beautifully and deftly told it is heartbreaking when the hero is sent back to the gulag. All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews (Faber) is wonderfully funny and tragic at the same time. Toews is a major talent and her novel grips the heart. The Forgiven by Lawrence Osborne (Vintage) is set mostly in Morocco and starts with an appalling incident in the foothills of the Atlas mountains as an English couple drive themselves to a lavish party. The tension is intense. Isaiah Berlin’s Affirming: Letters 1975-1997 (Chatto & Windus), edited by Henry Hardy and Mark Pottle, is probably the last volume Hardy will produce; it contains some wonderful letters and a huge dollop of Berlin’s capacious mind as well as his fondness for gossip. Man on Fire by Stephen Kelman (Bloomsbury) may be one of the most quirky books I have ever read. It concerns – in what turns out to be a true story – an Indian man, Bibhuti Nayak, who has plans to rise above the slums and poverty around him. One of these is to set out to see how many kicks in the crotch he can stand. It may sound bizarre, but it is also a revelatory and very touching book about India.

Us Conductors by Sean Michaels (Bloomsbury) won the Canadian Giller prize last year and is now published in Britain. It is a wonderful book, based on a true story of a Russian spy who lived in New York for some years between the wars, making a musical reputation while he was there as a pioneer of the theremin. His story is so extraordinary and so beautifully and deftly told it is heartbreaking when the hero is sent back to the gulag. All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews (Faber) is wonderfully funny and tragic at the same time. Toews is a major talent and her novel grips the heart. The Forgiven by Lawrence Osborne (Vintage) is set mostly in Morocco and starts with an appalling incident in the foothills of the Atlas mountains as an English couple drive themselves to a lavish party. The tension is intense. Isaiah Berlin’s Affirming: Letters 1975-1997 (Chatto & Windus), edited by Henry Hardy and Mark Pottle, is probably the last volume Hardy will produce; it contains some wonderful letters and a huge dollop of Berlin’s capacious mind as well as his fondness for gossip. Man on Fire by Stephen Kelman (Bloomsbury) may be one of the most quirky books I have ever read. It concerns – in what turns out to be a true story – an Indian man, Bibhuti Nayak, who has plans to rise above the slums and poverty around him. One of these is to set out to see how many kicks in the crotch he can stand. It may sound bizarre, but it is also a revelatory and very touching book about India.

Elizabeth Day

The Story of the Lost Child by Elena Ferrante; Hot Feminist by Polly Vernon; Curtain Call by Anthony Quinn

So many of my female friends were raving about Elena Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child (Europa Editions) that I read all four of her Neapolitan novels in a month. I was swallowed up whole by Ferrante’s writing: the intensity of it, the unapologetic focus on every rendered nuance of a lifelong female friendship. I’ve never read anything quite like it. It is so, so good on women: the ones trapped by men and violence and the ones who break free, with all the associated costs. Hot Feminist by Polly Vernon (Hodder & Stoughton) is bold, brilliant, sharp and funny, tackling big issues (rape, abortion, equal pay) in fizzing prose. Part memoir, part polemic, it urges women to be less judgmental – of each other and of themselves. It’s an idea that shouldn’t be revolutionary but is. I loved Curtain Call by Anthony Quinn (Vintage). Ostensibly a murder mystery set in 1930s London, it is also a multiple character study of wonderful depth and wit. I cannot wait for the sequel, Freya, out in March 2016. The book I’d most like to be given for Christmas is David Lodge’s memoir, Quite a Good Time to Be Born (Harvill Secker). I’m a big fan of Lodge’s work and think he’s criminally underrated as a writer. And it’s an exceptionally good title for a memoir. Or quite a good one at least.

So many of my female friends were raving about Elena Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child (Europa Editions) that I read all four of her Neapolitan novels in a month. I was swallowed up whole by Ferrante’s writing: the intensity of it, the unapologetic focus on every rendered nuance of a lifelong female friendship. I’ve never read anything quite like it. It is so, so good on women: the ones trapped by men and violence and the ones who break free, with all the associated costs. Hot Feminist by Polly Vernon (Hodder & Stoughton) is bold, brilliant, sharp and funny, tackling big issues (rape, abortion, equal pay) in fizzing prose. Part memoir, part polemic, it urges women to be less judgmental – of each other and of themselves. It’s an idea that shouldn’t be revolutionary but is. I loved Curtain Call by Anthony Quinn (Vintage). Ostensibly a murder mystery set in 1930s London, it is also a multiple character study of wonderful depth and wit. I cannot wait for the sequel, Freya, out in March 2016. The book I’d most like to be given for Christmas is David Lodge’s memoir, Quite a Good Time to Be Born (Harvill Secker). I’m a big fan of Lodge’s work and think he’s criminally underrated as a writer. And it’s an exceptionally good title for a memoir. Or quite a good one at least.

Sara Wheeler

Circling the Square by Wendell Steavenson; The Ancient Art of Growing Old by Tom Payne

Wendell Steavenson’s Circling the Square (Granta) is a gripping memoir of a foreign correspondent’s years covering the Egyptian revolution and its aftermath; I found it more nuanced than a media report could ever be. I also enjoyed Tom Payne’s The Ancient Art of Growing Old (Vintage Classics), a humorous guide to classical authors’ advice on the downhill catwalk of age. In my stocking, to savour during the fug, I hope to find Helen Simpson’s new collection of short stories, Cockfosters (Jonathan Cape).

Wendell Steavenson’s Circling the Square (Granta) is a gripping memoir of a foreign correspondent’s years covering the Egyptian revolution and its aftermath; I found it more nuanced than a media report could ever be. I also enjoyed Tom Payne’s The Ancient Art of Growing Old (Vintage Classics), a humorous guide to classical authors’ advice on the downhill catwalk of age. In my stocking, to savour during the fug, I hope to find Helen Simpson’s new collection of short stories, Cockfosters (Jonathan Cape).

Julie Myerson

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara; In My House by Alex Hourston; The Little Red Chairs by Edna O'Brien

It’s overlong, and underedited, but I was still blown away by Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (Picador) – a life-changing read. Alex Hourston’s In My House (Faber) is a fantastically assured first novel: suspenseful, offbeat and deeply original. And Edna O’Brien’s The Little Red Chairs (Faber) is the kind of masterpiece that reminds you why you read books in the first place. For Christmas? Please, please could someone publish Nancy Reisman’s beautiful and haunting novel Trompe L’Oeil – currently only available in the US from Tin House – so she can have the audience in the UK she deserves?

It’s overlong, and underedited, but I was still blown away by Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (Picador) – a life-changing read. Alex Hourston’s In My House (Faber) is a fantastically assured first novel: suspenseful, offbeat and deeply original. And Edna O’Brien’s The Little Red Chairs (Faber) is the kind of masterpiece that reminds you why you read books in the first place. For Christmas? Please, please could someone publish Nancy Reisman’s beautiful and haunting novel Trompe L’Oeil – currently only available in the US from Tin House – so she can have the audience in the UK she deserves?

Kate Kellaway

A Place of Refuge by Tobias Jones; Another Mother's Son by Janet Davey

Tobias Jones’s A Place of Refuge (Quercus) is a wonderful book describing the bosky – sometimes bolshie – community he and his wife set up for allcomers: recovering alcoholics, addicts and anorexics. It is written with the keenest eye for nature – human and leafy – and a wisdom learned the hard way (perhaps there is no other way). Janet Davey’s Another Mother’s Son (Chatto & Windus) is funny, shrewd and desolating – a novel that makes you look and think twice. For Christmas, I’d like Helen Simpson’s new short stories: Cockfosters (Jonathan Cape).

Tobias Jones’s A Place of Refuge (Quercus) is a wonderful book describing the bosky – sometimes bolshie – community he and his wife set up for allcomers: recovering alcoholics, addicts and anorexics. It is written with the keenest eye for nature – human and leafy – and a wisdom learned the hard way (perhaps there is no other way). Janet Davey’s Another Mother’s Son (Chatto & Windus) is funny, shrewd and desolating – a novel that makes you look and think twice. For Christmas, I’d like Helen Simpson’s new short stories: Cockfosters (Jonathan Cape).

Salley Vickers

Breezeway by John Ashbery; In Certain Circles by Elizabeth Harrower; Music, Sense and Nonsense by Alfred Brendel

The lyrics in Breezeway, a new collection by the octogenarian poet John Ashbery (Carcanet), are as good as his finest. I especially like the final poem, poignantly reprising the last line of Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale, “Do I wake or sleep?” In Certain Circles by Elizabeth Harrower – a subtle psychologist, whose novels have been rediscovered by the Australian publisher, Text. Music, Sense and Nonsense (Biteback) by Alfred Brendel – not only an extraordinary musician but also an illuminating commentator. For me, Imagined Cities by Robert Alter, please (Yale).

The lyrics in Breezeway, a new collection by the octogenarian poet John Ashbery (Carcanet), are as good as his finest. I especially like the final poem, poignantly reprising the last line of Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale, “Do I wake or sleep?” In Certain Circles by Elizabeth Harrower – a subtle psychologist, whose novels have been rediscovered by the Australian publisher, Text. Music, Sense and Nonsense (Biteback) by Alfred Brendel – not only an extraordinary musician but also an illuminating commentator. For me, Imagined Cities by Robert Alter, please (Yale).

Chris Mullin

After the Storm by Vince Cable; Margaret Thatcher: Everything She Wants by Charles Moore

I enjoyed After the Storm (Atlantic), Vince Cable’s thoughtful sequel to his earlier bestseller on the global financial crisis, both for what it says about the state of the nation and for its occasional insights into life in the coalition government. Also, Margaret Thatcher: Everything She Wants (Allen Lane), the second volume of Charles Moore’s monumental biography is a must for all Thatcherologists. For light relief, I am looking forward to reading Gun Street Girl (Serpent’s Tail), the latest thriller from Adrian McKinty, an Irish author who is belatedly beginning to enjoy the recognition he deserves.

I enjoyed After the Storm (Atlantic), Vince Cable’s thoughtful sequel to his earlier bestseller on the global financial crisis, both for what it says about the state of the nation and for its occasional insights into life in the coalition government. Also, Margaret Thatcher: Everything She Wants (Allen Lane), the second volume of Charles Moore’s monumental biography is a must for all Thatcherologists. For light relief, I am looking forward to reading Gun Street Girl (Serpent’s Tail), the latest thriller from Adrian McKinty, an Irish author who is belatedly beginning to enjoy the recognition he deserves.

Julian Baggini

The Health Gap by Michael Marmot; Saving Capitalism by Robert B Reich; The Meaning of Science by Tim Lewen

Two important books on inequality convinced me this year – Michael Marmot’s The Health Gap (Bloomsbury) and Robert B Reich’s Saving Capitalism (Knopf) – of our potential to achieve transformative change in politics without overthrowing the entire system of democratic capitalism. In contrast, Tim Lewens’s The Meaning of Science (Pelican) is a wonderful example of how a so-called introduction can in fact be a brilliant summation of all that matters. For Christmas, I’d like a break from words, and the images in Rosamund Kidman Cox’s 50 Years of Wildlife: Photographer of the Year (Natural History Museum) are just awe-inspiring.

Two important books on inequality convinced me this year – Michael Marmot’s The Health Gap (Bloomsbury) and Robert B Reich’s Saving Capitalism (Knopf) – of our potential to achieve transformative change in politics without overthrowing the entire system of democratic capitalism. In contrast, Tim Lewens’s The Meaning of Science (Pelican) is a wonderful example of how a so-called introduction can in fact be a brilliant summation of all that matters. For Christmas, I’d like a break from words, and the images in Rosamund Kidman Cox’s 50 Years of Wildlife: Photographer of the Year (Natural History Museum) are just awe-inspiring.

Damian Barr

The Last Act of Love by Cathy Rentzenbrink; Not My Father's Son by Alan Cumming

Cathy Rentzenbrink’s The Last Act of Love (Picador) is a heartbreaking memoir detailing the awful living death of her beloved brother, Matty. It is sad but never depressing and ultimately inspiring. The same is true of Alan Cumming’s memoir, Not My Father’s Son (Canongate). It’s about as far from a sparkly, celeb self-massage as you can get, and tells how he survived his abusive father and went on to thrive in the style we know and love. Can someone please give me The Early Stories of Truman Capote? (Penguin)

Cathy Rentzenbrink’s The Last Act of Love (Picador) is a heartbreaking memoir detailing the awful living death of her beloved brother, Matty. It is sad but never depressing and ultimately inspiring. The same is true of Alan Cumming’s memoir, Not My Father’s Son (Canongate). It’s about as far from a sparkly, celeb self-massage as you can get, and tells how he survived his abusive father and went on to thrive in the style we know and love. Can someone please give me The Early Stories of Truman Capote? (Penguin)

John Banville

Affirming, ed. by Hardy and Pottle; Empire and Revolution by Richard Bourke; Vivid Faces by Roy Foster; Satin Island by Tom McCarthy