|

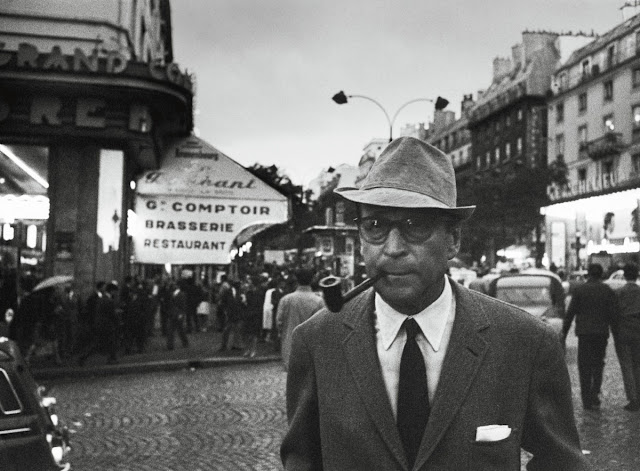

| Georges Simenon Paris, 1962 |

The genius of Georges Simenon

As he brings one of the crime writer’s novels to the National stage, David Hare reveals why he loves the pithy, power-obsessed creator of Maigret

David Hare

Sunday 25 September 2016 08.00 BST

L

ike many bookish children, I grew up consuming detective fiction more than any other kind. Even then I had noticed that stories supposedly driven by narrative depended for their real vitality on establishing ambience. Crime writing came to life when it had density, when you felt that the paint was being laid on thick. A strong sense of time and place was far more exciting than a clever puzzle. Anyone could create a mystery, but only the best could summon up a world in which the mystery could take root.

My taste in literary fiction – I read every word of Patrick Hamilton and Graham Greene – was towards those authors whose techniques most closely resembled those of thriller writers. When, at university, I came across WH Auden’s suggestion that Raymond Chandler’s books “should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art”, I was bewildered. It had never occurred to me that thrillers were anything less. By then I had already graduated from Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers to Dashiell Hammett and the chill ambiguity of Patricia Highsmith. But when I discovered that the author of the Maigret series – which I knew chiefly through the BBC television series with Rupert Davies – was also the author of stand-alone novels, my expectations of the genre changed and expanded. These books belonged more alongside Camus and Sartre than Arthur Conan Doyle. The popular joke in Le Canard enchaîné that “M Simenon makes his living by killing someone every month and then discovering the murderer” seemed nothing more than that. A joke.

It’s symptomatic of our misunderstanding of the unique Georges Simenon that so many people believe he was French. In fact, he was Belgian, born in Liège in 1903 and brought up in a poorly defined country that had often suffered under occupation. In Belgium, few people fostered illusions about national greatness. “Under occupation,” he wrote, “your overwhelming concern is with what you will eat.” Simenon’s background, and his lifelong feeling that he was disliked by his mother, left him with the aim of developing, equally as a writer and as a man, a wholly undeluded view of life. As he later observed: “It must be great to belong to a group, a nation, a class. It would give you a feeling of superiority. If you’re alone you’re not superior to anyone.” Or as he put it rather more bitterly: “During earthquakes and wars and floods and shipwrecks you see a love between men that you don’t see at any other time.”

In fact, he could hardly have been less French. What Frenchman or woman would speak of their loathing of gastronomy – “all that terrible fussing about what you eat”? What French writer or politician would agree that “every ideal ends in a fierce struggle against those who do not share it?” Simenon was particularly horrified by Charles de Gaulle’s pretence that the French had won the war. The untruth offended him. Simenon believed the events of the 1930s and 40s had defeated the French as thoroughly as they had the Germans. “I’ve ceased to believe in evil, only in illness. Nixon believes he’s the champion of the United States, De Gaulle the rebuilder of France. Yet nobody locks them up. Those who invent morals, who define them and impose them, end up believing in them. We’re all hopeless prisoners of what we choose to believe.”

Simenon, not prone to grand literary statements, once said that he wanted to write like Sophocles or Euripides. Over and again, he describes someone quietly living their life, until some random fait divers – a road accident, a heart attack, an inheritance – brings out a fatal element in their character that trips them up. Striking out towards freedom, they fall instead into captivity. He had the idea that a book, like a Greek tragedy, should be experienced in a single session. “You can’t see a tragedy in more than one sitting.” Serial killers, soon to become the thundering cliches of modern drama, whether speaking Danish, Swedish or English, would have held no appeal for Simenon precisely because they are, by definition, extraordinary – and considerably less common in life than on television. Typically, in one of Simenon’s stories, a single crime is enough to ensure that a hitherto normal life falls apart, with no notice, as though any of us might at any time suddenly encounter a crisis that we will turn out to be powerless to overcome.

The thrill of reading a novel, said Simenon, is to “look through the keyhole to see if other people have the same feelings and instincts you do”. The man who, when adolescent, says he suffered physical pain at the idea that there could be so many women who would escape him, has the intense focus of a voyeur. An ex-journalist, he often describes towns from their canals or railway lines, because from there you could look into the back of residents’ lives and not be deceived by the front. He may have said “Other people collect stamps, I collect human beings”, but remarkably he refuses at all times to pass judgment on anyone. “You will find no priests in my work!” Not only does Simenon take care to exclude politics, religion, history and philosophy from his character’s dialogue and thoughts, but the deadpan flatness of his prose style and his bare-bone vocabulary create a disturbing absence of moral control. “Fifty years ago people had answers, now they don’t.”

It was this fallen universe of compromise that I found so convincing when I was growing up. It matched what I had already seen of life. I knew at first hand that Simenon was right when he said that “the criminal is often less guilty than his victim”. But it was only when I was older that I became addicted to the hard stuff – the unsparing novels that take his fatalistic view to its ultimate. If, as is generally thought, Simenon wrote around 400 books, then about 117 are serious novels, the romans durs that meant most to him. André Gide, one of his many literary admirers, when asked which of Simenon’s books a beginner should read first, famously replied: “All of them.” But to my own taste, Simenon’s most searching work came out of his queasy, compromised time in occupied France, and in his desperate hunt thereafter for personal happiness in heavy-drinking exile in the US. If you want to read three of his greatest books, try the deceptively light Sunday, written in 1958 about a Riviera hotel-keeper who spends a year preparing to kill his wife; try The Widow, published, like The Outsider, in 1942, and at least equal to Camus’s work in portraying a doomed and alienated life; and above all be sure to read Dirty Snow, a story of petty crime and killing at a time of collaboration in a country that remains unnamed, but which is always taken to be France under the Nazis.

Because he was foolish enough in an interview to claim to have slept with 10,000 women – the real figure, said his third wife rather crisply, was nearer 1,200 – Simenon has sometimes been accused of misogyny, just as by allowing films to be made of his books at the Berlin-supervised Continental Studios in Vichy France during the war, he was also accused of collaboration. The charge of misogyny at least is unfair. A small man’s fear of women is often his subject, and he describes that fear with his usual pitiless accuracy. In his books, casual sex is fine – it may or may not be satisfying – but passion is always dangerous because it arouses feelings neither party can control – and loss of control is seen to be a particularly masculine terror. In these circumstances, sex comes closer to despair than to joy. The women he portrays are not usually manipulative or cruel or deceitful. Far from it. They simply possess an inadvertent power to disturb men and to drive them mad. They exercise this power more often in spite of themselves than deliberately. All of his books are, in one way or another, about power of different kinds, and he specialises in depicting the lives of those near the bottom of society, the concierges and the salespeople, the waiters and the clerks, who possess very little. No wonder, when he went to America, that he remarked how everyone was expected to have a hobby, so that in one small field at least they might exercise at least a measure of domination.

The inspiration for finally deciding to write a play from Simenon came from my friend Bill Nighy, who knew that I was a fan. He gave me a present of a rare first edition of a novel that had been almost entirely forgotten. Even now, I have yet to meet anyone in Britain who claims to have read La Main. In Moura Budberg’s translation, long out of print, the book had been published as The Man on the Bench in the Barn. It was written in 1968, but its atmosphere clearly derived from Simenon’s own period of residence in Connecticut, where he moved to live with his new wife, Denyse Ouimet, in the late 1940s. In the book, the town he then lived in, Lakeville, is renamed Brentwood. His house, Shadow Rock Farm, becomes fictionally Yellow Rock Farm. But the topography and feel of the place are pretty much identical, with beavers playing in a nearby stream, and the local Connecticut community expecting strong but already threatened standards of private morality. The only detail omitted was Simenon’s own telephone number: Hemlock 5.

We hear a lot about Henry James and the Americans’ traditional fascination with Europe. We hear rather less about its opposite. In my view, there is something rare and interesting artistically when a European sensibility engages with American morals. La Main describes America at a point of change, when the suburban world patrolled so brilliantly by writers such as Richard Yates, Sloan Wilson and Patricia Highsmith is about to yield to a newer way of life, theoretically freer but equally treacherous. It was characteristic of Simenon to suspect that sexual liberation might not deliver everything it promised. After all, he doubted most things, except his own writing. But it was even more characteristic of Simenon to be in the right place, as he had been in France and Africa before the war, and at the right time, equipped with a reporter’s calm genius for putting a moment in a bottle.

No comments:

Post a Comment